Philanthropy as a Long-Term Social Practice

Before delving into specific avenues, one might conceive of a more general thing called philanthropy than mere incidence of charitable bumps. Bestowing has been an act performed in tandem with political systems, economic conditions, and cultural expectations throughout history. The form may change; the consequences build throughout history, manner of often being uncertain as to whether everything should be attributed to one donor or given moment.

Sustaining a philanthropic institution that works, on the other end of the spectrum, does not ritualize relationships such as in mere commercial transactions. It develops a continuum involving generations of givers, institutions, and beneficiaries, creating webs of responsibility that stretch across individual lifetimes.

From Immediate Relief to Enduring Institutions

Short-term giving tends to focus on urgent needs: disaster relief, emergency medical care, or temporary shelter. These responses are essential, but they rarely reshape the systems that produced vulnerability in the first place. Long-term philanthropy shifts attention toward institutions that address root causes, such as education, public health infrastructure, and cultural preservation. Over time, these investments change how societies respond to need, often reducing dependence on crisis-driven support.

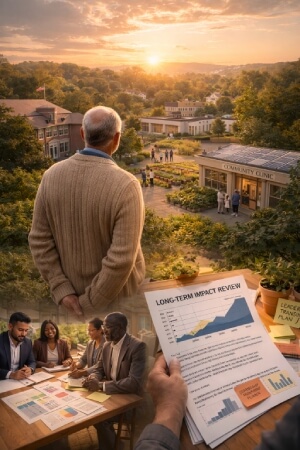

Enduring institutions usually begin modestly. A school, clinic, or community program may rely on early philanthropic support before becoming self-sustaining or publicly funded. The impact of such efforts is cumulative rather than dramatic. Decades later, their presence may feel ordinary, even inevitable, which can obscure the philanthropic commitment that made them possible in the first place.

Time Horizons and Generational Thinking

Taking the long view requires donors to think beyond personal timelines. Many philanthropic outcomes will not be visible within a single lifetime, particularly those involving education, environmental stewardship, or social norms. This generational perspective can feel counterintuitive in cultures that value quick results and measurable returns. Yet some of the most consequential philanthropic work accepts delay as part of its design.

Generational giving also introduces questions of stewardship. Foundations, trusts, and family endowments must balance honoring original intent with adapting to changing circumstances. The challenge lies in maintaining purpose while allowing strategies to evolve. When done well, this approach enables philanthropy to remain relevant without becoming rigid or detached from current realities.

The Slow Accumulation of Trust and Capacity

Long-term philanthropy depends heavily on trust, which develops slowly and can be lost quickly. Communities are more likely to engage with philanthropic initiatives when they see consistent presence rather than intermittent attention. Repeated engagement signals commitment and respect, allowing organizations to build local capacity rather than impose external solutions.

Capacity building is rarely visible in annual reports. It involves training staff, strengthening governance, and creating stable funding structures. These efforts may not generate compelling headlines, but they determine whether organizations can adapt, survive leadership changes, and respond effectively to future challenges. Over time, this quiet work often proves more influential than high-profile gifts.

Collective Giving and Shared Responsibility

Philanthropy scholarships, often associated with definition in terms of individual donors, take on another dimension with participation by the group. With giving established as the norm rather than receiving recognition from others, it creates an expectation of mutuality or mutual obligation. Local communities engaged in collective giving have more robust civic connections and institutions.

Collaboration does not erase representation in terms of scale or any influence, but it rephrases giving as a confluent process and not just top-down giving.

How Pooled Resources Extend Impact

Collective giving allows smaller contributions to support larger ambitions. Community foundations, mutual aid funds, and cooperative grantmaking models pool resources to address complex issues that exceed the capacity of individual donors. This approach spreads risk and encourages collaboration among donors who might otherwise act independently.

Pooling resources also enables experimentation. When responsibility is shared, organizations can test new ideas without relying on a single benefactor’s tolerance for risk. Over time, successful models can be refined and expanded, while unsuccessful ones provide lessons rather than failures. This iterative process strengthens the overall philanthropic landscape.

Norms, Culture, and the Expectation of Participation

When philanthropy becomes culturally embedded, participation feels expected rather than exceptional. In such contexts, giving is seen as part of citizenship, not an optional expression of personal virtue. This shift influences how people relate to institutions, public goods, and one another.

Cultural norms around giving often develop through visibility and repetition. Schools, workplaces, and local organizations play a role in reinforcing these expectations by normalizing volunteerism and shared support. Over time, these habits shape how societies respond to inequality, crisis, and opportunity, making generosity a collective reflex rather than an individual decision.

Balancing Voice and Equity in Group Giving

Collective philanthropy raises important questions about power and representation. Decisions about funding priorities, evaluation, and governance must account for diverse perspectives to avoid reproducing existing inequalities. Without careful design, pooled resources can still reflect the preferences of a narrow group.

Equitable collective giving requires transparency and mechanisms for shared decision-making. Including community voices in planning and oversight helps ensure that long-term investments align with lived experience. While this process can be slower and more complex, it often produces outcomes that are better adapted to local needs and more sustainable over time.

Why Sustained Giving Matters More Than One-Off Action

Here, the highest quality operates at the slowest rate. Both of them need to develop steadily. The second issue mainly addresses the future for gift cycles of a year or a decade. Startup social ventures are likely to survive in a climate of social disrespect for institutional growth.

This situation keeps people under-invested even though this inaction produces a loss to the greater good.

Stability as a Prerequisite for Meaningful Change

Organizations working on complex social issues require predictable support to plan effectively. Sporadic funding forces them into short-term thinking, diverting energy toward survival rather than strategy. Sustained philanthropy provides the stability needed to invest in staff, infrastructure, and long-range goals.

Stability also allows for honest evaluation. When funding is ongoing, organizations can acknowledge setbacks without fear of immediate withdrawal. This environment encourages learning and adaptation, which are essential for addressing deeply rooted challenges. Over time, steady support often yields more durable outcomes than large but isolated gifts.

Learning Over Time and the Value of Persistence

Philanthropic work rarely follows a straight line. Programs evolve, assumptions are tested, and external conditions change. Sustained engagement allows donors and organizations to learn together, refining approaches based on evidence and experience.

Persistence signals commitment to the underlying mission rather than to a specific tactic. When donors remain engaged through periods of uncertainty or slow progress, they reinforce trust and continuity. This patience can be particularly important in areas such as social inclusion or environmental protection, where progress is incremental and setbacks are common.

Avoiding the Cycle of Attention and Abandonment

One-off philanthropy often mirrors cycles of public attention. Issues receive funding when they are visible and lose support when interest shifts. This pattern can leave organizations struggling to maintain momentum or meet ongoing needs.

Sustained giving counters this dynamic by decoupling support from headlines. It allows organizations to focus on long-term objectives rather than short-term visibility. Over time, this approach contributes to a more balanced distribution of resources and reduces the volatility that can undermine social programs.

What Durable Philanthropy Looks Like in Practice

Durable philanthropy is not defined by a single model or philosophy. Instead, it reflects a set of practices that prioritize continuity, accountability, and adaptability. These practices can be observed across different sectors and scales, from local initiatives to global foundations.

Below are common characteristics that tend to appear where philanthropy has lasting influence:

- Long-term funding commitments that extend beyond annual cycles

- Clear governance structures that balance intent and flexibility

- Regular evaluation focused on learning rather than compliance

- Investment in people and institutions, not just projects

- Openness to collaboration and shared leadership

These elements do not guarantee success, but they create conditions where learning and resilience are possible. They also help philanthropy remain responsive without becoming reactive.

The Responsibility That Comes With Taking the Long View

There also rests responsibility in any conversation about extreme philanthropy. Decisions that are being taken now have consequences over several generations, at times in ways unintended. There is thus an observance in appreciation of humility, introspection, and derail when necessary.

This long and calculated vision of philanthropy brings into being the realization that donors could still hold sway long after they have left, putting stewardship on seemingly equal footing with intent.

Accountability Across Time, Not Just Outcomes

Traditional accountability often focuses on immediate results: outputs delivered, funds spent, targets met. Long-term philanthropy expands this frame to include institutional health, community relationships, and unintended consequences. Accountability becomes an ongoing conversation rather than a final report.

This broader view requires systems that track progress without reducing complex change to simple metrics. It also demands transparency about uncertainty and limits. Over time, such practices strengthen credibility and allow philanthropy to contribute constructively to public life rather than operate in isolation.

Adapting Without Losing Purpose

Durability does not imply rigidity. Social conditions change, and philanthropic strategies must evolve in response. The challenge lies in adapting methods while maintaining clarity of purpose. When organizations cling too tightly to original plans, they risk irrelevance. When they abandon purpose entirely, they risk mission drift.

Effective long-term philanthropy establishes guiding principles rather than fixed solutions. These principles provide continuity while allowing experimentation. Over decades, this balance enables philanthropy to remain aligned with its values while responding to new knowledge and circumstances.

Recognizing When to Step Back

Taking responsibility for long-term impact also includes knowing when to reduce or end involvement. Continued funding is not always the best outcome, particularly when programs have achieved sustainability or when local leadership is ready to take full ownership.

Stepping back thoughtfully can be as important as sustained support. It requires planning, communication, and respect for partners. When done well, it reinforces autonomy rather than dependency and allows philanthropic resources to be redirected where they are most needed.

Giving That Outlasts the Moment

When viewed in the long term, the assistance extended by charity reflects its true potential and realizable sustenance. Gifting so transform the institutions, norms, and capacities that it is these, and not the gifts and donors, that precede them much later on the timeline of future construction and development! With sustainability in mind, sharing amongst stakeholders, and being more proactive, philanthropy could possibly metamorphosize the stereotype into an agent of capacity building within societies.